Confessions of an almost venture backed founder

On narratives, impact, and the elusive “founder” stereotype

Prelude: apologies for the (long) silence. This post took a lot longer to write than I was anticipating. I also want to recognize that the below piece shares one of many perspectives on the venture-backed founder path, and I totally respect anyone who decides to go down the path. I hope that, more than anything, my post helps folks considering this path go in with eyes wide open to the possibilities. Now, without further ado, back to our scheduled programming…

I don’t remember the first time I considered becoming a venture-backed founder. You know, the kind of founder that rolls to meetings in a black t-shirt and jeans, or a Patagonia sweater if they have fashion sense (and by they I mean he, because let’s be real, most founders in the Valley are white dudes). The kind of founder that shares advice like “move fast and break things” or “stay paranoid” that sounds so simple yet profound at the same time.

Maybe it was seeing my own brother go through the founder journey, Stanford’s strong entrepreneurial history (especially in the CS department), or jealousy over my classmate’s founder success, but I became captivated by this path. It felt like the most accessible, scalable way for me to leave a robust legacy while utilizing my privilege and talents, something my immigrant parents had strongly emphasized throughout my childhood. I didn’t know exactly how I would impact people’s lives, but my naiveté was an asset. Technology was a tool that would disrupt every industry, and many industries have been disrupted by people who have never worked in that industry. Maybe it could be multiple. It also helped that when I shared my plan with my classmates, I could see the respect in their eyes. Like- this girl is ambitious. She wants to make shit happen. And that was a version of me that I liked.

During the first three years of my career, I spent most of my free time outside of work brainstorming spaces and potential solutions. I interviewed nonprofits in the women’s empowerment space. I pitched a gift card donation startup. I led a design sprint about civic engagement. I started a blog interviewing social impact founders. I explored building tools to help victims of sexual harassment and assault with a friend. But I was grasping for straws. I didn’t know if I cared deeply enough about these ideas to commit the next five or ten years of my life. Or if the problem was painful enough to be worth solving or “big enough” business. There was, as always, a voice in the back of my head that asked me if starting a company was really what I was meant to do. This questioning led me to punt on brainstorming and go work at an actual mission driven startup to learn the ins and outs of running a company. I told myself that while I wait for the right idea to strike, I could spend the time learning the ins and outs of running a company. Looking back, I think I was looking for validation on whether startups were really what I wanted to do.

The Shift.

So, what did I learn?

The short answer is that I’ve become disillusioned by venture-backed startups as a vehicle to maximize user impact.

The longer answer is that I don’t think that a scale-maximizing impact is the type of impact I want to pursue given the negative externalities of the process. Even for the most user-minded companies, it introduces tensions that eventually prioritizes profit over impact, disincentivizes employee health and morale through a false sense of urgency and corporate performativity, and the immense (sometimes unrealistic) pressure on the founder leads to great personal sacrifice, which I’m not convinced is worth it.

Let’s deep dive into each of the elements.

Tension of profit vs impact.

VC investment mechanics require pushing each company in the portfolio to 10x their investment, even though a handful of companies in their portfolio will actually achieve that level of revenue. This means that impact-oriented startups aren’t just focused on generating revenue or achieving sustainability, but 10x’ing their investors' investment. This is only possible via hypergrowth mechanics (i.e. hiring more people, pursuing more business lines, etc.), which introduce scenarios where the best-intentioned founders feel pressured to prioritize growth over people (whether employees or customers). In my experience, this can show up in small ways (deprioritizing polish or rushing to ship something new without considering all edge cases) and big ways (shipping a product that uses anti-patterns to drive adoption), especially when the company starts running low on runway.

Additionally, even if a venture-backed startup can overcome the business pressures, there’s always going to be limitations to the type of impact technology can have. Technology can reduce friction and improve accessibility of information, thereby amplifying existing human behavior (example here with political organizing). But making something easier or more accessible isn’t always sufficient to create real, lasting change, especially for systemic social problems. I saw this limitation first-hand in my own work at Propel. While we built technology that made the lives of folks on government benefits a bit easier through managing their EBT benefits, that’s a pretty small and minimal fraction of the challenges in their lives. This sentiment showed up in user interviews, when we asked them what else we could to help them, the problems were rooted in bigger, systemic problems in the financial and government benefits systems (like how the government determines eligibility for certain benefits or lack of childcare infrastructure in the US). While I don’t think social impact companies should be responsible for fixing systemic issues in our society (nor do I think they can), it led me to question if we wanted to truly improve the lives of this population, then are the problems that technology is poised to solve the ones that will lead to real, transformational change.

False sense of urgency aka corporate performativity

While not unique to startups, I think they are particularly susceptible to this because there’s often this notion that startups need to “move quickly” which worsens the false sense of urgency. It also leads companies to deprioritize the difficult conversations on how the work gets done, since the ROI of that time isn’t as clear as shipping or selling software.

In the beginning, assuming the founding team is on good terms, prioritization and product/business decisions are easy to resolve, since it’s a small group of people. But as the company grows, the lack of clarity in updated structures or responsibilities results in a false sense of urgency. This is especially worse at startups as many early employees (who have often not managed people) are promoted into positions of leadership, despite lacking the management experience, resulting in an incohesive strategy and structure. This means that individual contributors like me have to spend time navigating the politics as much as making the right decisions, resulting in more time getting buy-in, showing other people what you’re working on, or not pushing back due to the power dynamics involved. Balancing all these competing demands while working at the breakneck speed of startups is draining, resulting in chronic bouts of burnout.

I also think this phenomenon is particularly insidious at startups because there’s a lot more ownership assigned to each individual. One startup showed me my total comp in terms of the future valuation of the company to make it clear that my work could help shape the total value of the company. Combine that with the small size, it’s hard not to feel personal responsibility towards outcomes, even when you might not have the full ownership or responsibility to shape those outcomes. But while this thinking helps companies get the most out of their employees, it’s not great for worker’s mental health. I certainly burned out multiple times during my startup career when it felt like no matter what I did, it was never going to be good enough to achieve the outcomes.

In other words, the goal post feels like it’s constantly moving.

Personal sacrifice

My biggest learning from this journey? Being a founder is one of the most isolating, lonely experiences. You can’t ever be your true self with your employees, since you’re supposed to be their boss. You feel completely responsible for the future of the company, customers and employees. The buck stops with you, yet you need to learn to delegate and empower others, which can often make it feel like you have very little control. You have a boss (the board), but it’s a boss that you need to manage, especially as your role evolves.

Most founders I worked for or have gotten to know are incredibly anxious, hiding behind an overconfident persona, which is the only way they get their initial funding. But behind the mask, there were tell-tale signs of anxiety: greying hair, never-ending dark circles, poor eating habits, or panic attacks. I’m already a pretty anxious person, and I don’t know if the pressures and complications of this path would be the best companion to my existing mental health challenges.

In some ways, the sacrifice is valiant. To give up so much of your identity and mental wellbeing for the success of your company is a lot. It also fits the traditional “hero” narrative persistent in American culture that probably brings a deeper sense of validation. It must feel so satisfying to communicate to others, especially strangers, that you’re the superhero in the story of your career.

But if you zoom out, and take into account the mixed impact on employees and customers, it’s not clear to me if the journey is worth it for me.

Looking Forward.

While I’ve ruled out the venture backed founder path, I still love the idea of entrepreneurship. Having the ownership to build something from scratch is exhilarating. But if I was to become an entrepreneur, I’d want to do it on my own terms. I want to pursue the type of entrepreneurship that centers the mission and lifestyle first and growth and profits second, challenging notions like the necessity of quarter over quarter growth. Some folks call it a “bootstrapped” or “lifestyle” business, but to me, it’s less about lifestyle and more about finding a balance between my values and ambitions.

But there’s a lot to figure out in pursuing this new kind of entrepreneurship. For example, what’s the way that I define my impact? Scale is easy to latch onto because it’s easy to measure. But scale can also be isolating. I felt that past a certain number, the numbers feels hard to grok and feel, and once I got to the point, it became less about the humans behind the numbers and more about the validation from moving the numbers in a certain direction that made me feel like I had “impact.” This realization is resulting in exploring other kinds of impact, specifically:

Narrative impact: utilizing storytelling to give voice to novel perspectives/people/situations. Using stories to inspire people to expand their horizons about certain topics/questions. For example, one topic that I’m particularly excited to explore is the invisible power dynamics in everyday interactions that ladder up to larger traumas or insecurities.

Direct impact: spending a lot of high-touch time working with folks to empower and help them get unstuck. Previously, I associated this with “playing small” because of the lack of emphasis on scale. However, the more I focus on 1:1 individual work, the more I realize that there’s an understated “butterfly effect,” where the changes your presence makes then inspires that person to help others, multiplying the impact of your work. That allows me to reconcile my need for scale with feeling the human behind the impact.

There’s still a lot to unpack with these newfound realizations, such as how I build a career that maximizes for this impact while not compromising on my lifestyle goals. But even writing these words, I can feel something expanding in my body, for the first time in a long time. And that to me is probably the most important signal than anything else.

Special thanks to and for inspiring me to convert our conversations and early notes on this topic to an essay. Also, thank you Avi for reading an earlier version of this essay :)

Thing of Note

Recap: This section is my way of bringing attention to a thing, person, or idea that’s meaningful/related to the mission of this newsletter. This week, I want to highlight Wanting by Luke Burgis.

This book has made me feel incredibly seen, especially as I navigate this ambiguous career break period. The thesis of this book is that mimesis underlies all of our desires- that what we want is directly influenced by what others want. In fact, it’s often argued that the root of all violence is mimetic desire (which is definitely a bold claim, but kind of makes sense if you think about it). I definitely resonate with this (case and point: my dead founder dreams). But can we ever find something that we want that isn’t influenced by others? That’s what the book tries to explore. I’m still on the first part of the book that dives more into the theory behind mimetic desire, and haven’t gotten to the practical tips part, but it’s been an eye-opening journey in terms of unpacking my own desires for why I want certain things, especially as I redefine my relationship with achievement. Definitely recommend reading or listening to it as an audiobook!

Thanks for Reading!

I’m on a journey to create a blended career across the creative arts, tech, and business. This newsletter is my way of sharing my reflections, thoughts, and advice along the way. Here are some ways to support or further collaborate together!

I would love feedback on this post.

If you want to see more content like this, heart the post.

Hearing from readers also gives me a ton of energy. Drop a comment if you are assessing if the venture-backed startup path is for you, or any realizations about impact.

If you’re figuring out your own career transition or looking for more support in your product career, consider working with me as a coach. Here’s my calendly if you want to get the ball rolling.

This was a great reflection + analysis!

Your perspective on "bootstrapping" was eye-opening. I've always thought of bootstrapping as a VC-backed startup with a different capital structure, but the same principles. I prefer your view that it's "more about finding a balance between my values and ambitions". This is a much better lens - thanks for sharing!

"I certainly burned out multiple times during my startup career when it felt like no matter what I did, it was never going to be good enough to achieve the outcomes."

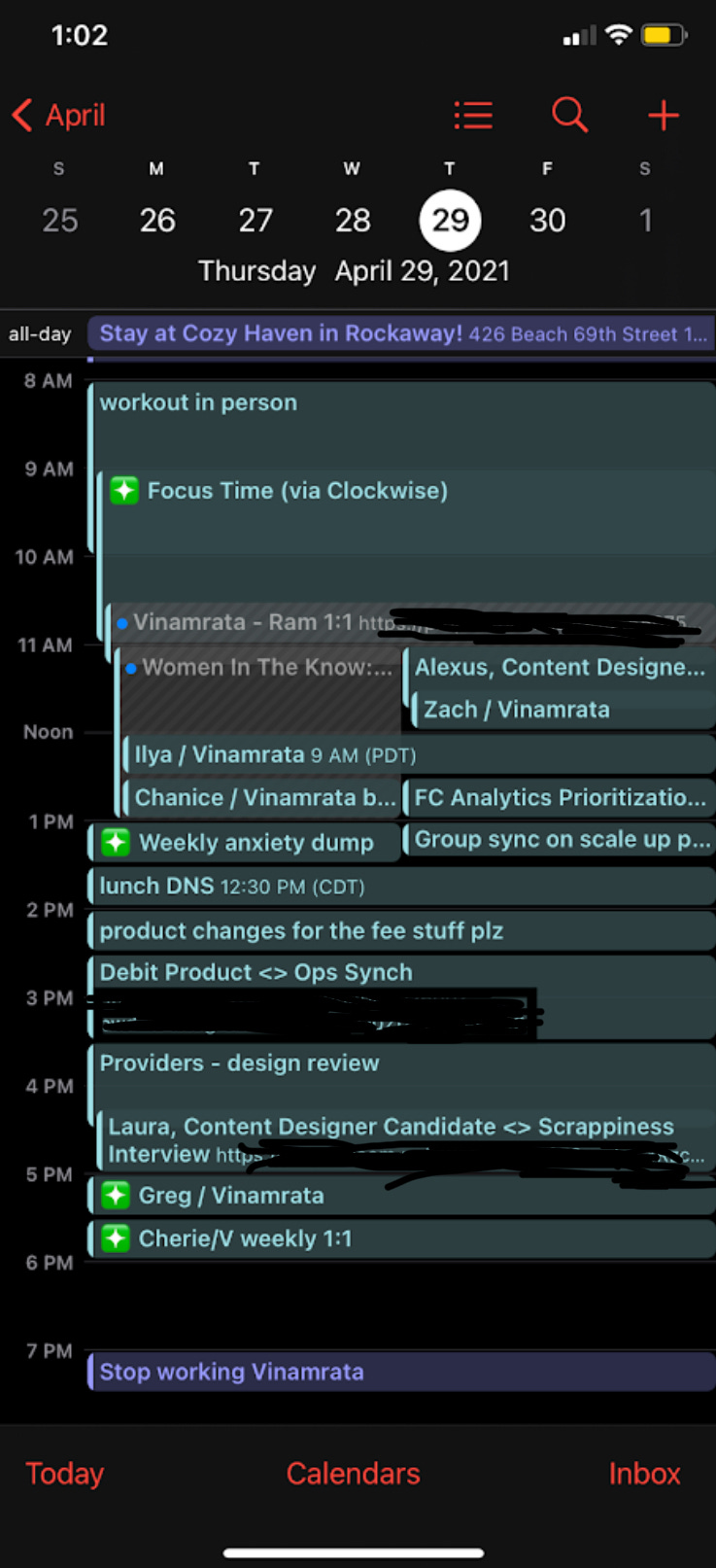

This, along with your screenshot of your calendar really captured the feeling of busy and overwhelm that's so present in work today.

I'm looking forward to following along on your journey to build a career that maximizes impact without compromising on lifestyle goals, I'd love the answer too!